What you should know about Swimmer’s Itch

What is it?

Swimmer’s itch (cercarial dermatitis) is a skin irritation caused by a larval form of certain flatworms from the family Schistosomatidae.

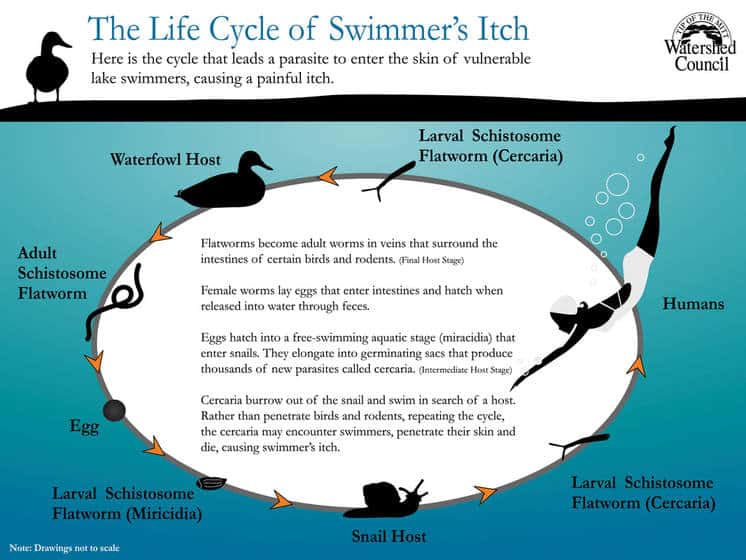

Schistosome flatworms are parasites with a complex life cycle usually involving certain species of snails and waterfowl. Upon hatching, free swimming Schistosomatidae larvae seek out an intermediary host, usually snails, to continue the life cycle. The skin condition occurs when larvae mistakenly burrow into human skin. The larvae, known as cercariae, are only 1/32 of an inch long and generally invisible to the naked eye. Since humans are not the proper host, the larvae soon die upon burrowing into the skin. The itching sensation is caused by an immune response to the dead larvae under the skin and responses vary by person.

Many species of parasitic flatworms are naturally occurring in most lakes. However, not all larval species cause swimmer’s itch. The life cycle and host requirements of those species responsible for swimmer’s itch differ widely, and the natural history of most is poorly understood. In North America, at least 30 states and parts of Canada have documented the skin condition. In the United States, the problem appears to be concentrated in the most northern tier of states.

Many species of parasitic flatworms are naturally occurring in most lakes. However, not all larval species cause swimmer’s itch. The life cycle and host requirements of those species responsible for swimmer’s itch differ widely, and the natural history of most is poorly understood. In North America, at least 30 states and parts of Canada have documented the skin condition. In the United States, the problem appears to be concentrated in the most northern tier of states.

Where does it come from?

The life cycle of the flatworm involves two very specific hosts. Each flatworm often uses just one species of snail and one kind of waterfowl as intermediate and definitive hosts to complete its life cycle. Both must be present in the same lake for the life cycle to be completed.

What are the symptoms?

Not all people are sensitive to swimmer’s itch. Some who are exposed to the larvae never develop the itch. Those who are sensitive may feel a dull, prickly sensation as the larvae burrow into the skin. This may occur either while swimming or immediately after leaving the water. At each point of entry a small red spot may appear and begin to itch.

Not all people are sensitive to swimmer’s itch. Some who are exposed to the larvae never develop the itch. Those who are sensitive may feel a dull, prickly sensation as the larvae burrow into the skin. This may occur either while swimming or immediately after leaving the water. At each point of entry a small red spot may appear and begin to itch.

Symptoms include intermittent periods of itching that will continue for several days. Many suffering from swimmer’s itch experience the most severe itching early in the morning. Usually the reddened areas reach their largest size after approximately 24 hours. The itchy, reddened, and raised areas are sometimes confused with bites from chiggers or mosquitoes and the symptoms may be misdiagnosed as those resulting from poison ivy or stinging nettles. Chigger bites are usually located at points where clothing contacts the skin such as wrists, waist, ankles, etc. For swimmer’s itch, itching is limited to points of cercarial entry and will not spread or develop into water blisters.

Swimmer’s itch, although extremely annoying and uncomfortable, is not a communicable or fatal condition. Over-the-counter drugs are available to reduce the symptoms of swimmer’s itch. Antihistamines can be used to help relieve the itching while topical steroid creams may help to reduce the swelling. Before taking any of these drugs, however, consult your physician or dermatologist for advice.

Controlling Swimmer’s Itch

Since the life cycle of the flatworm depends on the presence of both of its two intermediate hosts, the elimination of either will block reproduction. The traditional method of controlling swimmer’s itch has been to attempt to kill the host snails with copper sulfate. A permit from Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) in Lansing is required prior to any aquatic use of the compound.

Since the life cycle of the flatworm depends on the presence of both of its two intermediate hosts, the elimination of either will block reproduction. The traditional method of controlling swimmer’s itch has been to attempt to kill the host snails with copper sulfate. A permit from Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) in Lansing is required prior to any aquatic use of the compound.

Copper sulfate is a nonspecific poison which means that it is toxic not only to snails, but also to many non-target aquatic plants and animals. Copper, a toxic heavy metal, accumulates in lake sediments and can bioaccumulate in the living tissues of aquatic animals. Long-term, heavy applications of copper sulfate can pose a significant threat to the health of aquatic environments.

Copper sulfate treatments often don’t kill enough of the target snails to eliminate swimmer’s itch. There is also some evidence that snails may be capable of developing resistance to copper sulfate. Despite the application of tens of thousands of pounds of copper sulfate in some lakes during the past 50 years, the occurrence and severity of swimmer’s itch has not noticeably diminished. An interesting study done by Freshwater Solutions, LLC biologists in 2017 showed there was no decrease in risk of contacting swimmer’s itch after a copper sulfate treatment (publication coming in 2018).

NOTE: The Tip of the Mitt Watershed Council does not endorse or encourage the use of copper sulfate to prevent or control Swimmer’s Itch.

Alternatives to Copper Sulfate

One effective approach to controlling swimmer’s itch was developed by Dr. Harvey Blankespoor of Hope College in Holland, Michigan in the 1980s. His method involves removing the resident summer ducks, most often common mergansers, from a lake and relocating them to one of the Great Lakes where the snail host is absent.

Harvey has passed the swimmer’s itch control torch to his son, Dr. Curt Blankespoor of the University of Michigan Biological Station. Working with a team of 5 Ph.D. biologists, they have trapped and relocated all resident common mergansers off Higgins Lake (Roscommon County, MI) since the summer 2015. The lake-wide snail infection levels have dropped more than 98% over that time period, and not surprisingly, both the number and severity of reported swimmer’s itch cases have also dramatically declined. See a summary of the Higgins Lake 2015-2017 data.

Control programs utilizing this method have been carried out on several lakes. The incidents of swimmer’s itch were greatly reduced compared to pre-treatment levels. www.MISIP.org.

Another control method being used in our service area is Merganser Control Programs. As part of the Walloon Lake Association’s Swimmer’s Itch Initiative, the association hired a wildlife management company to hunt mergansers during the 2009 fall hunting season. They removed 60 mergansers that were primarily resident birds to Walloon Lake. Wildlife biologists were also hired to harass mergansers in the spring of 2010, before they nested on Walloon Lake. This helped reduce the number of mergansers on the lake, this year and in subsequent years, thus reducing the level of the parasite that causes swimmer’s itch.

Freshwater Solutions, LLC also created safer swim areas by using floatable baffles to enclose a swim area and then removing the snails within the enclosure or manually destroying the larvae in the water. See the Leelanau Project 2017 Annual Report for more details.

What can our lake association do about swimmer’s itch?

It can do several things including the following: educate members about swimmer’s itch, assess the problem of swimmer’s itch on its lake, make recommendations for relieving the itching, and begin a control program if swimmer’s itch is a regular problem.

Preventing Swimmer’s Itch

There are several means by which you can significantly reduce your chances of contracting the swimmer’s itch parasite.

- Since itch-causing larvae usually live in the shallows near the shore, it is best to avoid these areas as much as possible. This is especially important when the wind is blowing toward the shore.

- Towel off thoroughly as soon as you leave the water and at frequent intervals. The fragile cercaria of some species can sometimes be rubbed off before they fully penetrate the skin.

- Do not feed waterfowl! Feeding waterfowl may aggravate the problem by concentrating potential hosts in a limited area.

- Maintain a healthy greenbelt along your shoreline property with a variety of native plants (including trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants) to prevent waterfowl from congregating on your property. Shading of near shore areas as a result of a shoreline greenbelt will also help reduce the amount of bottom-dwelling algae growth, which is a primary food source for the type of snails that are commonly hosts in the schistosome cycle.

Playlist

This is video #7 in the “Protecting What You Love” video series produced by Tip of the Mitt Watershed Council. The video focuses on the link between feeding waterfowl and swimmer’s itch.

Funding for this project provided by:

Charlevoix County Community Foundation

Petoskey-Harbor Springs Area Community Foundation

Crouse Entertainment Group

2017 Michigan Swimmer's Itch Partnership Conference

Michigan Swimmer’s Itch Partnership (MISIP) is a coalition of lake associations, formed in to reduce the incidence of swimmer’s itch in Michigan’s inland lakes. The videos in this playlist are the presentations from the 2017 MISIP Fall Conference held on September 18, 2017 at Hagerty Center, Traverse City, Michigan.