*Restricted in Michigan

Overview

Eurasian watermilfoil (Myriophyllum Spicatum) is a plant native to Europe and Asia that was first documented in North America in the mid 1940s. Since its introduction, it has spread to more than 40 states in the US and to three Canadian provinces. Unfortunately, Eurasian watermilfoil has invaded many Northern Michigan lakes including Burt, Long, Paradise, and Walloon Lakes.

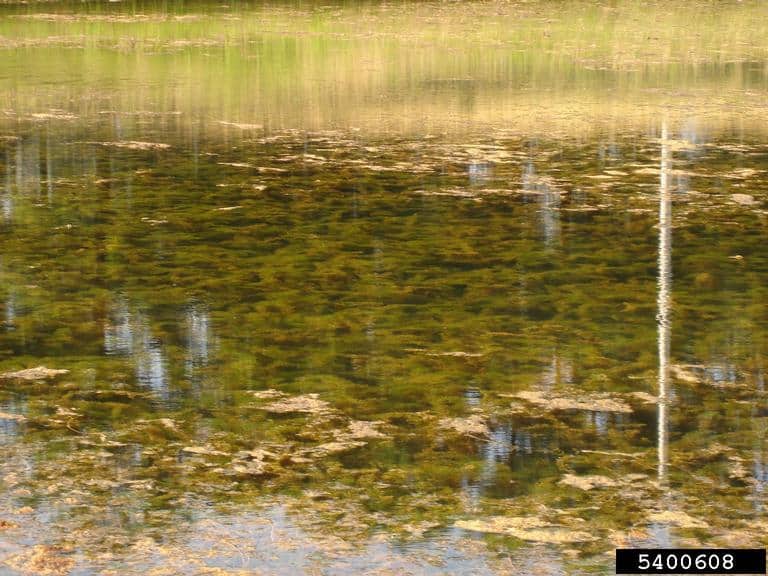

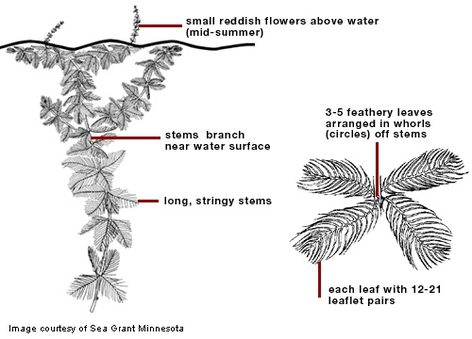

As Eurasian watermilfoil takes hold in a lake, it causes problems for the ecosystem and for recreation. It tolerates lower temperatures and starts growing earlier than other aquatic plants, quickly forming thick underwater stands of tangled stems and vast mats of vegetation at the water’s surface. These dense weed beds at the surface can impede navigation – and no one likes to swim in areas thick with aquatic plants. The lake ecosystem suffers because Eurasian watermilfoil displaces and reduces native aquatic plant diversity, which is needed for a healthy fishery. Infestations can also impair water quality due to dissolved oxygen depletion as thick stands die and decay.

A key factor in the plant’s success is its ability to reproduce through both stem fragmentation and underground runners. Eurasian watermilfoil spreads to other areas of a water body by fragmentation. A single stem fragment can take root and form a new colony. Locally, it grows by spreading shoots underground.

Boat traffic is responsible for the majority of introductions into new water bodies and for spreading the plant. Watermilfoils commonly become entangled in boat propellers, attach to keels and rudders of sailboats, and get caught up in boat trailers. Stems that become lodged in watercraft and trailers are transported to other water bodies, which is all that is needed to colonize new water bodies. Boats also contribute to unnatural seasonal fragmentation and the distribution of fragments throughout infested lakes.

Eurasian watermilfoil has difficulty becoming established in lakes with well established populations of native plants. In some lakes, the plant appears to coexist with native flora and has little impact on fish and other aquatic animals. Removing native vegetation, whether physically or with herbicides, creates the perfect opportunity for invading Eurasian watermilfoil.

Table of Contents

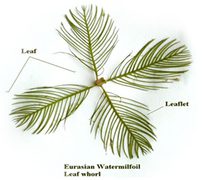

Identifying Eurasian Watermilfoil

What you can do to prevent the spread of this invasive species

- Learn to identify Eurasian watermilfoil

- Inspect and remove aquatic plants and animals from boat, motor and trailer

- Drain lake or river water from livewell and bilge

- Rinse boat and equipment with high-pressure hot water (104° F), especially if moored for more than a day, or dry everything for at least 5 days

- Report sightings of Eurasian Watermilfoil to Tip of the Mitt Watershed Council by calling (231) 347-1181 or by e-mail at info@watershedcouncil.org . Please note the exact location in which you saw the species.

Control Methods

There are several techniques used to control nuisance aquatic plants, but most are not effective or practical for Eurasian watermilfoil. Manual or mechanical removal can exacerbate the situation because of the plants ability to colonize through fragmentation. Benthic barriers (shown left), placed over the plants, have been installed in Higgins Lake with fairly good results. Herbicides may be suitable for spot application, but are not recommended for large infestations due to ecosystem-wide impacts and uncertainties regarding the impacts of chemicals on non-target aquatic organisms and humans. Biological control using a native weevil is the safest ways to control Eurasian watermilfoil, but can be costly depending on the degree of infestation and effectiveness of treatment. Ultimately, prevention is the most effective and least expensive strategy for controlling Eurasian watermilfoil, as well as all other invasives.

Biological – Native Weevils

Early detection through monitoring/aquatic plant surveys

Education and Prevention

This is video #11 in the “Protecting What You Love” series created by Tip of the Mitt Watershed Council. Eurasian watermilfoil (Myriophyllum Spicatum) is a native to Europe and Asia that was first documented in North America in the mid 1940s. Since its introduction, it has spread to more than 40 states in the US and to three Canadian provinces. In this video you will learn how to identify Eurasian Watermilfoil and learn about control methods to prevent the spread of this invasive species.

Funding for this video was provided by:

Charlevoix County Community Foundation

Petoskey-Harbor Springs Area Community Foundation

Crouse Entertainment Group

Youtube Video Insert